Saturday, January 12, 2013

SCIBERRAS, A. (2012) Fauna regarded as domestic pests in the Maltese islands (10) - The Feral Pigeon. The Malta Independent, December 17th pg 4-5.

We Maltese in general rarely see birds locally as pests, but we tend to see them as welcomed visitors and while a minority enjoys their company by observing them in the wild, the majority love to enjoy them gathering dust on shelves as sport trophies. I am more than sure that the practice of shooting birds has struggled to continue for the latter reason and not for food consumption. Therefore, birds should be considered much less as pests. Arnold Sciberras writes.

Locally, the only three species usually considered as agricultural pests are the following three species: the Spanish Sparrow (Passer hispaniolensis), Għasfur tal-Bejt, is usually considered a pest in fields as it gathers in large numbers to feed on agricultural products. It easily gets used to objects installed to scare it. In fact local farmers tend to nick name it as ‘ġurdien bil- ġwienaħ’ (mouse with wings), and this is because of the latter’s destructions and also due to its cunningness of a mouse. The only nuisance caused by this bird as a domestic pest is that it tends to see ventilators as the cradle for its offspring. Besides the nest which sometimes makes a foul smell, other arthropods usually follow within it. Nest material tends to be bulky, blocks the ventilator and nest material starts entering the house. Despite all this, it is illegal to disturb in any way this species as it is protected by law. Nearly the same applies for the Starling (Sturnus vulgaris ) Sturnell, except that it does not breed in ventilators and that in some time of the year it may be legally recognized as a bird applicable for hunting.

On the other hand the Feral pigeon, (Columba livia domest) Ħamiem Selvaġġ, is considered to be both an agricultural and domestic pest, and most tend to blame the latter for fouling most facades of buildings within towns and cities and for carrying certain diseases. As agricultural pests, they eat adequate quantities of agricultural products and they tend to spread diseases from one farm to the other. Most farmers nick name pigeons ‘firien tas-sema’ (rats of the sky).

Feral pigeons are derived from domestic pigeons that have returned to the wild. The domestic pigeon was originally bred from the wild Rock Pigeon, also known as Rock Dove, which naturally inhabits sea-cliffs and mountains. All three easily interbreed. Feral pigeons find the ledges of buildings to be a substitute for sea cliffs, and have become adapted to urban life and are abundant in towns and cities throughout most of the world.

Many city squares are famous for their large pigeon populations. Such city squares include the Piazza San Marco in Venice and Trafalgar Square in London. For many years, the pigeons in Trafalgar Square were considered a tourist attraction, with street vendors selling packets of seeds for visitors to feed the pigeons. The feeding of the Trafalgar Square pigeons was controversially banned in 2003. However, activist groups such as ‘Save the Trafalgar Square Pigeons’ flouted the ban, feeding the pigeons from a small part of the square .The organisation has since come to an agreement to feed the pigeons only once a day, at 7.30am. In the Maltese archipelago this species is fairly abundant in all localities but tend to have impressive numbers at Valletta, Floriana, ta’ Xbiex, Imsida, Ħamrun, Victoria (Gozo) and on Comino (caves under pig farm and the cliff and islet known as Tal-Mazz).

Pigeons breed when the food supply is good. For wild Rock Doves this might be seasonal so they usually breed once a year. In the wild they are often found in pairs in the breeding season but usually they are gregarious. In the urban environment, because of their year-round food supply, feral pigeons will breed continuously, laying eggs up to six times a year.

Feral pigeons can be seen eating grass seeds and berries in urban areas and gardens in the spring, but there are plentiful sources throughout the year from scavenging (e.g. dropped fast-food cartons) and they will also eat insects and spiders. Further food is also usually available from the disposing of stale bread in many locations by restaurants and supermarkets, from tourists buying and distributing birdseed, etc. Pigeons tend to congregate in big groups when going for discarded food, and many have been observed flying skillfully around trees, buildings, telephone poles and cables, and even moving in traffic just to reach it.

As a result of the continuous food supply, pigeon courtship rituals can be observed in urban areas at any time of the year. Males on the ground initially puff up feathers at the nape of the neck to increase their apparent size and thereby impress or attract attention, and then they single out a female in the vicinity and approach with a rapid walk while emitting repetitive quiet notes, often bowing, sweeping their opened tails on the floor and turning as they approach. Initially, females invariably walk away or fly short distances while the males follow them at each stage. Persistence by the male will eventually persuade the female to tolerate his proximity, at which point he will continue the bowing motion and very often turn full- or half-pirouettes in front of the female. Subsequent mating is very brief, with the male flapping his wings to maintain balance on the female. Sometimes the male and female beaks are locked together.

Buildings are used for nesting as are cliffs and other natural sites. Favourite nesting areas are in old or damaged property. Mass nesting is common with dozens of birds sharing a building. Loose tiles and broken windows give pigeons access. They are remarkably good at spotting when new access points become available, for example after strong winds cause property damage. Nests and droppings will quickly make a mess of any nesting area. Pigeons are particularly fond of roof spaces, many of which accommodate water tanks, though they frequently seem to fall into the tanks and drown. Any water tank or cistern in a roof space needs to have a secure lid for this reason. The popularity of a nesting area seems little affected if pigeons die or are killed there; corpses are seen among live birds, which seem unconcerned.

On undamaged property the gutters, window air conditioners (especially empty air conditioner containment boxes), and external ledges will be used as nesting sites. Many building owners attempt to limit roosting by using floating empty plastic bags held by thin rope, bird control spikes and netting to cover ledges and resting places on the facades of buildings. These probably have little effect on the size of pigeon populations, but can help to reduce the accumulation of droppings on and around an individual building.

Feral pigeons tend to vary tremendously in plumage colours. Some of these morphs were even named and even local variants are known to occur. In Malta the author observed over 7 different morphological morphs that are generally persistent to occur.

This species belong to the family Columbidae. In Malta 7 species are recorded, all of which are protected by law except one which is hunted seasonally and the feral pigeon. These species are: the Woodpigeon (Columba polumbas) Tudun Ewropej, the Rockdove (Columba livia) Tudun Tal-Ġebel (ancestor of all domestic and feral pigions; most probably, Rock Doves do not occour locally as a pure breed), the Stock Dove (Columba oenas) Tudun Tas-Siġar, the Turtle Dove (Streptopelia turtur) Gamiema Komuni, the Collared Dove (Streptopelia decaocto) Gamiema Tal-Kullar, the Palm Dove (Streptopelia senegalensis) Gamiema tal-Ilwien/tal-Palm and the Barbary Dove (Streptopelia risoria) Gamiema tal-Bar/Ġar (originated from escaped stocks).

Pigeons have been falsely associated with the spread of human diseases. Contact with pigeon droppings poses a minor risk of contracting histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and psittacosis. Pigeons are, however, at potential risk of carrying and spreading avian influenza. Although one study has shown that adult pigeons are not clinically susceptible to the most dangerous strain of avian influenza, the H5N1, other studies have presented definitive evidence of clinical signs and neurological lesions resulting from infection. Furthermore, it has been shown that pigeons are susceptible to other strains of avian influenza, such as the H7N7, from which at least one human fatality has been recorded.

Note: This series of articles was intended to cover and give a brief overview of the most common groups of local species that regarded as pests. Obviously much more species than those mentioned in this series are regarded as pests in our islands and some have high economic value. I coined the articles as ‘domestic pests’ to cater those that have an impact on domestic households and other establishments.

Those pests that have an impact on the agricultural sector can be one of these listed in the series or others that are more specific to the latter. Unfortunately there are several other species that are all except pests, most of which are beneficial, but due to their appearance, habits and association with superstitious beliefs, they are regarded as pests. Most of these species are also protected by law. The emblem representative of the latter may be the geckos, (wiżgħat). I would like to thank Romario, Jeffrey and Esther Sciberras for their general assistance in compiling this work.

For more information: http://arnoldsciberras.blogspot.com ,bioislets@gmail.com or 99887950.

SCIBERRAS, A., SCIBERRAS, J. & Pisani, L. (2012) Selmunett under siege again! The Malta Independent, December 10th pg 12.

about a month ago - Monday, 10 December 2012, 09:09 , by Arnold Sciberras, Jeffrey Sciberras and Luca Pisani, Nature Trust (Malta)

The rats are back! And this time with a vengeance. This story has being going on since the late 90s, but now it’s gotten worse. The Brown Rat (Rattus norvegicus) is an invasive creature and if left unchecked it may harm local species and delicate ecosystems. One such ecosystem is that of Selmunett Island, better known amongst locals as St Paul`s Island. The island, including its biodiversity, is scheduled as a Special Area of Conservation - Candidate Site of International Importance via Government Notice 112 of 2007, as declared through the provisions of the Flora, Fauna and Natural Habitats Regulations of 2006 (Legal Notice 311 of 2006).

Selmunett Island (St Paul Island) was designated as a Nature Reserve via LN 25 of 1993. Il-Gżira ta' San Pawl / Selmunett has also been declared as a Specially Protected Area under the SPA Protocol (Barcelona Convention) since 1986. However, this jewel of an island, so rich in archaeological and natural history, has been left in a disastrous state. One may ask who is responsible. We hate pointing fingers to the authority, but let’s face it, one or the other has to take a step forward. We as public are also to blame because if it is something that is happening at our doorstep,we quickly go complaining but when it is of a national and in this case even an international level we just shut one eye and let things slide. Since the ecological state of the island has reached a critical level further degradation must be stopped immediately.

Our surveys on this island date back to the late 90`s, when the island already had its fair share of rodents, but their existence had not yet taken its toll. However as history has taught us, if these creatures are left unchecked then this island and other similar sites are doomed. The rats succeeded in driving the lizard endemic to Selmunett (Podarcis filfolensis subsp. kieselbachi) to extinction, and now threaten other wildlife.

Efforts from both naturalists and the respective authority had managed to halt the destruction of this species through bait control. Yet now, what were once rodent traps have become little more than accumulated rubbish, and due to a lack of maintenance, the rats have once again taken over, evidently destroying anything in their path. All the work done to control these invaders has been in vain. The French Daffodil (Narcissus tazetta) having been a very common species on the island, as well as one of particular interest (since it was observed by the authors to flower slightly before those of the mainland) lately seems to be decreasing in numbers.

The extensive digging habit of the rodents, clearly shown by the large amount of holes that cover the island, is a great hint to the fact that they dig up and gnaw on the underground bulbs and roots of the French Daffodil and other herbaceous species. After the attempts of rodent eradication, some species such as the Turkish and Moorish geckos (Hemidactylus turcicus &Tarentola mauritanica) were augmenting back, but ultimately they also started to fall prey to the rats once again. Besides numerous burrowed holes, their faeces is everywhere, and their sightings have increased so drastically that even the un-trained eye can easily spot these creatures, and one must watch out who crosses the footpaths first!

To make things worse, rats are not only the ecological aliens on the island. Attempts to eradicate the foreign cactus Opuntia stricta, a smaller relative of the Prickly Pear (Opunita ficus-indica), have also proven to be a waste of time, since the uprooted stems of Opuntia strictawhere not removed from the island, but left on the ground. With such a great tendency for the majority of succulents to root themselves easily, the left-overs formed plants of their own, and ironically, this aided and not diminished their numbers on the island. Like all succulents, Opuntia stricta can smother any native species of plant. Another alien succulent species left unchecked on the island is the American Agave (Agave americana), which has already conquered its own patch of ground. This is a massive species not to be reckoned with, and if left to its own devices, the island will end up with a similar fate to Baħar iċ-Ċagħaq. Another note, this time from a historical point of view, is that the farmhouse which symbolises human existence on the island is in great need of restoration, as in the last decade it has almost completely fallen apart. This structure, if properly restored, could well be used as an observation centre on the island and its wildlife!

There may be still some hope of saving the island, but words alone are not enough. If we truly want the island to remain a Special Area of Conservation - Candidate Site of International Importance, then let’s take action before it’s too late!

SCIBERRAS, A.(2012) The summer of Maltese sea turtles. The Malta Independent, December 3rd pg 15

Summer 2012 will always be the time that I will associate with sea turtle experiences around the Maltese Islands. This is not because it is my first experience to encounter a sea turtle, by far my first recollection of a sea turtle sighting was at the age of 9. However, this year it was the highest count of sea turtle sightings that I gathered. Moreover, the largest specimen of the Loggerhead Turtle, Carretta carretta, I ever saw in my life time and undoubtedly in Maltese Islands was in this year. It is also the first time, not just for me, but for most of us, to experience the Loggerhead Turtle nesting in our islands. For me it seemed that this nesting was more of an accident, rather than intentional, since normally a cautious adult female turtle would never climb on a beach with flood lights everywhere, dispose its eggs so close to the sea shore and scram so fast that it will hit a floater on the way out to sea.

This is what happened to the presumably lost turtle that on 20.6.12 landed on Ġnejna bay, came on the beach, laid 79 eggs (almost half a nest) and fled back to sea. As Sciberras and Deidun (in Caruana, 2012) stated that probably this specimen was heading to Lampedusa and it got lost or could not wait to deposit the eggs till the end of the trip. I doubt that it was a released rescued turtle or that it was born in this location, due to the fact that the previous nesting was recorded at Ġnejna in 1915. It is documented that, not so in the distant past, marine turtles used to lay eggs on sandy beaches such as at Ramla l-Ħamra, in Gozo, and Santa Marija Bay, in Comino. A more recent laying is said to have occurred at Golden Bay (Ramla tal-Mixquqa) in 1960 (Deidun and Schembri, 2005) when the eggs were dug up and, with mother turtle finished, cooked by some local Neanderthals.

Whatever the case was, it happened and I think for once (unlike the recorded past) I must say the Maltese public acted maturely, and besides recording the event, they did not disturb the turtle nor the nest. The same cannot be said to the officials as they feared that the eggs were too close to the water and this may harm the eggs. This is partially true, but when you assess the period when the eggs were laid and the implications when moving the eggs at that time, I would have personally decided not to touch them.

If there was no alternative I would have put first in mind the eggs, and I would have never buried them in the same overpopulated and very active beach but transfer them to a more quite pristine pocket beach or hatched them in captivity. I could have even tried to take them to Lampedusa, because I feel that currently no local beach is available for this species to breed. However, as I am writing this article and all the event had passed including the eggs not hatching for mostly natural agencies, I feel that it would have been wrong that if it was possible things went my way.

This is not from an ecological point of view obviously, but from the cultural development that I observed, which took place during this whole story. As I witnessed the public becoming aware quickly of the situation, government and non government entities performed an excellent job in stipulating temporary enforcement laws and physical protection, but this time the applause should also go to the general public.

The vibe in the air that was noted at Ġnejna and all over the island, including the importance that was given by the media was phenomenal. As naturalists we find it hard to get any public support, not even in the simplest events, but this time when we asked for volunteers to stand by the egg watch, the list was flooded by interested people ready to participate. The public generally respected the boundary for the nest protection site and many were continuously asking volunteers if they require any help and asking at the same time general questions about the natural history of the species. The turtle adoption pack by Nature Trust (Malta) was never this successful, and the curiosity and interest amongst most individuals was oddly surprising. Most of public also proved to be law abiding during these two months.

Local summer residents and visitors alike informed me that this was their best summer yet because they enjoyed less traffic, less pollution (noise, light or otherwise) and they prayed that a turtle will nest each year for such a summer to repeat itself! What I enjoyed most was there was a sense of pride amongst most people that I discussed the issue with. As a nation we became more educated towards environmental conservation and we are lucky that such a majestic species provided us with such an experience. Alas, this wilted towards the end because of the fear that the eggs will not hatch, in which it became a reality. Yet again more good than bad came out of the whole event. I myself enjoyed several close encounters with wandering sea turtles during coastal snorkelling, but never would I have imagined that by the end the summer, there will be a sighting of the biggest specimen I had ever encountered.

On 7.10.12 I was at Rabat police station in Gozo reporting a different matter when a turtle rescue call came about. I rushed to Dwejra to see the situation when I encountered a couple who were snorkelling in the limits of Fungus Rock. They recounted the story; as they were snorkelling, this gentle 50kg giant approached the couple slowly as if asking for help. Ralph Felice and Annabelle Attard quickly noticed the fishing lines where coming out of its rear end and that the animal looked in pain. Moving such a giant close to shore was no easy task and the latter took care of the animal in water for hours. When I and my colleges (Jeffrey Sciberras and Luca Pisani) found the couple, it was a pain stalking procedure to pull out such a heavy animal out of the water and carrying it up a hill way where a Gozo Police vehicle was waiting for it.

The vehicle was necessary to carry this majestic animal straight to Mġarr so Nature Trust members and Mepa Officials could take this animal for care to San Luċjan in Marsaxlokk from Ċirkewwa. Great caution was taken not to cause the animal anymore pain and to keep it wet. Cooperation between officials and public was again seen as its best for nature protection. As the patrol boat headed back to its berth the AFM Operations Centre was informed that a yacht had had found another injured turtle near Ġnejna. The crew handed the turtle to the sailors on the patrol boat, who later handed both turtles to Nature Trust and Mepa officials at Ċirkewwa quay. The same patrol boat, P-32, last week recovered an injured Greater Flamingo close to Baħar ċ-Ċagħaq. I hope that both turtles make excellent quick recoveries followed by a release in the wild, and I hope we will have a similar summer next year with more sightings, nestlings and less rescues of these beautiful relics.

I close this chapter by metioning again the enthusiasm and sensation these animals caused to the Maltese public when three rescued turtles, after a full recovery for several months at San Luċjan, were released from Ġnejna Bay on 9.10.12. A negative sensation was also caused when an adult turtle was found dead on 7.11.12 at Mgarr in Gozo. Death of this protected species seem to be caused by a tyrant who tied the animal and let the poor creature drown thus sufficate to death. I hope these stories will become a thing of the past and the initial story of this article will became frequent news.

Arnold Sciberras is Fauna Conservation Officer of Nature Trust Malta

SCIBERRAS, J. & SCIBERRAS, A (2012) Wild pigeons and doves of the Maltese Islands. The Malta Independent, June 11th pg 9.

The majority of the locals believe that hardly any birds exist in the Maltese islands; except for sparrows and pigeons. In reality this is not the case, because just over 450 species of birds have been recorded in Malta, 52 of which often nest, while others visit irregularly.

Jeffrey Sciberras and Arnold Sciberras write

The number of wild pigeons and doves species (collectively known as Columbids) found locally is sufficient enough to make someone appreciate the rich biodiversity that our country sustains.

Most people, when thinking of the word ‘pigeon’, envisage city pigeons – unfortunately also sometimes referred to as 'rats of the sky’ or ‘rats with wings’– or think about the domestic pigeon breed known as Homer or homing pigeons. When it comes to the word ‘dove’, people immediately think of the migratory Turtle Dove which is prized game for hunters. This generic thought holds some truth, but certainly does not refer to all the species of doves and pigeons we encounter on the Maltese Islands. In fact, seven species of pigeons and doves occur in the wild on the Maltese Islands. In nomenclature, wild pigeons in Maltese are called ‘Tudun’, while domestic pigeons are called ‘Ħamiem’. The word ‘Tudun’ also specifically refers to the European Wood Pigeon. Three species of migratory and local wild pigeons occur here, including the largest species, which is the European Wood pigeon, Columba polumbus; the Rock Dove, Columba livia from which all the domestic races have derived, such as the Feral Pigeon, Columba livia (domest.) and the Stock Dove, Columba oenas, which is similar in appearance to Feral Pigeons, but has shorter black wing bars and eyes that are completely black, lacking the orange iris . The European Wood pigeon and the Stock dove are two migratory species which are both scarce and rare visitors, which have never been documented to breed on the Maltese Islands. In contrast, the Rock Dove frequently breeds in local cliffs, and unlike the other two species, it is a resident species. Unfortunately, it has become very rare to see pure-breed wild Rock Doves in Malta. This is due to the fact that this species has been domesticated for a long time (more than 5000 years) and many varieties and breeds have artificially evolved from it. Feral Pigeons are likely to be descendants of primitive domestic pigeons which escaped, managed to survive in the wild, and interbred with wild Rock Doves.

Feral Pigeons are distinguished from domestic breeds simply because, despite the multitude of colours, their morphology (not plumage) is almost identical to wild Rock Doves. Due to an explosive growth from Feral Pigeons, the species has become an exceedingly common bird on a global scale, but the pure wild race, at least in Europe, is quite rare and has a limited distribution along the cliffs of Northern Europe. In 2001, one of the authors (AS) made an attempt to breed the wild Rock Dove. While the breeding inside Għammieri was successful, reintroductions in the wild seemed difficult because Feral Pigeons have to be eliminated first, and Pure Rock Doves often fall target to Hunters.

Doves are morphologically smaller than Pigeons. Four species visit the Maltese Islands. The largest species is the Eurasian Collared Dove, Streptopelia decaocto, which until recently was considered as a rare visitor but is now an established breeding bird. This species has been extending its range all over Europe and hence it started to arrive here in large numbers and eventually started breeding here. It first established itself as a breeding bird at Għajn Żejtuna; but eventually it started spreading in various localities such as Addolorata Cemetery, Buskett, Lija, Attard, Pietá, Fawwara and even in Comino and Gozo. Given chance, this species will spread all over the islands within a few years because in addition to being a prolific species, migratory individuals have tendencies to join resident flocks. The second largest species is the European Turtle Dove, Streptopelia turtur, which migrates in large numbers but is very rarely granted a chance to nest, even though many attempts have been reported over the years. The third largest and rarest species is the Laughing (or Palm) Dove, Streptopelia senegalensis. Another dove found on the Maltese Islands is the Barbary Dove, Streptopelia risoria (domest.). It is debatable whether this species is a domesticated breed descendant from the African Collared Dove Streptopelia risoria roseogrisea, or a totally different species. This species has bred in the wild via escaped individuals and sometimes hybridises with the Eurasian Collared Dove.

Pigeons and doves are generally weary of humans but a few, including those mentioned, have adapted to live near humans and found urban life more suitable. The European Wood Pigeon and the Collared Dove withstand urban life, but the major cities around the world, are dominated by Feral Pigeons. Can anyone imagine cities without this bird? If it weren’t for mankind, this race would not have existed. Humans managed to raise wild Rock Doves in captivity. When the species became tame, by artificial selection, several breeds and plumages emerged, none of which ever existed before. The purposes of domestic breeds are several, namely as sources of food, such as the Broiler, for competition and sport such as the Homer, and for exhibitions such as fantails, Pooters, Dwarfs, and so on. Feral pigeons obtained the various plumages from domestic breeds, but regained the morphological characteristics of the original ancestors from wild Rock Doves. This species was one of several which also assisted the renowned naturalist Charles Darwin to formulate his theory regarding evolution.

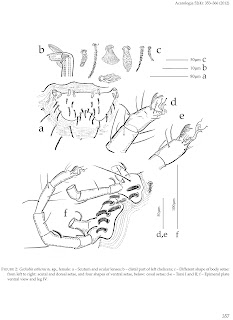

Many people assume that feral pigeons bring nothing but diseases, and these are considered to be a treat to architectural features, statues and buildings. It is true that their urban settings mean that they are not tidy and that their acidic faeces dissolves carbonic structures and to many bird breeders, naturalists and so on, the feral race is seen as a common species without any ecological value whatsoever. On the other hand to those interested in the classification of biodiversity, this race is a clear example of evolution. It is true that when a species evolves, it constantly changes to adapt to its environmental surroundings. The feral pigeon is not only a mix of coloured plumages which decipher nothing, but an array of forms, some of which persisted to exist and continued from one generation to another, in order to become distinct. This means that certain plumages have become standardised, and in some cases reached dominancy. From observations made by the authors, seven consistent varieties have been identified. Locally, the consistent varieties evolved in areas where the species is abundant, such as Valletta, Floriana, Ta' Xbiex, Msida, Ħamrun, Comino and Victoria (Gozo).So far no records or documents exist to show that these varieties are taxonomically recognized, except for the fact that feral pigeons can easily interbreed with wild Rock Doves . It is likely that certain varieties within time can become endemic. This has happened in places around the globe where species have become isolated. The varieties are morphologically pure, but not necessarily genetically pure as they can be interbred with other forms. Although it was noted that birds of opposite sexes are mostly attracted to similar plumages.

The so called ‘varieties’ are the following: nomenclature for such varieties is often colloquially used for describing individual birds in domestic breeds:

The rest of the forms that exist are intermediate between the mentioned consistent varieties, without any uniform pattern. Albinistic and melanistic forms occur. Albinistic flocks of pigeons are restricted to public gardens and farms. Melanistic pigeons are rare on the whole. Very rare forms sometimes seen are the Bronze, which is a likely descendant of the brown variety, and the Bluish-Red Bars are likely to be a cross between the Blue Bars and the Red Bars. Certain individuals are similar to any variety, but have odd characteristics such as white primary feathers, or irregularly placed white feathers on any part of their body, and these are referred to as Pied pigeons. With time, feral pigeon varieties outside Malta have become distinct subspecies. One example is Columba livia atlantis, which is found in Northern European countries along the Atlantic. Another example is found in England, at Trafalgar Square, where the entire population of feral pigeons evolved into the Dark Variety.

In recent years, some cities around the world started to implement measures to reduce the feral population of pigeons. This has become a necessity, in order to control the spread of disease, reduce genetic pollution with the original wild stock, and to prevent further damage to historical architecture. But at least it should be done in a humane or natural manner, such as reintroducing birds of prey that feed on feral pigeons. However, to some people the loss of feral pigeons from towns and cities is a big loss since it has become synonymous with urban infrastructures and societies.

Jeffrey Sciberras and Arnold Sciberras write

The number of wild pigeons and doves species (collectively known as Columbids) found locally is sufficient enough to make someone appreciate the rich biodiversity that our country sustains.

Most people, when thinking of the word ‘pigeon’, envisage city pigeons – unfortunately also sometimes referred to as 'rats of the sky’ or ‘rats with wings’– or think about the domestic pigeon breed known as Homer or homing pigeons. When it comes to the word ‘dove’, people immediately think of the migratory Turtle Dove which is prized game for hunters. This generic thought holds some truth, but certainly does not refer to all the species of doves and pigeons we encounter on the Maltese Islands. In fact, seven species of pigeons and doves occur in the wild on the Maltese Islands. In nomenclature, wild pigeons in Maltese are called ‘Tudun’, while domestic pigeons are called ‘Ħamiem’. The word ‘Tudun’ also specifically refers to the European Wood Pigeon. Three species of migratory and local wild pigeons occur here, including the largest species, which is the European Wood pigeon, Columba polumbus; the Rock Dove, Columba livia from which all the domestic races have derived, such as the Feral Pigeon, Columba livia (domest.) and the Stock Dove, Columba oenas, which is similar in appearance to Feral Pigeons, but has shorter black wing bars and eyes that are completely black, lacking the orange iris . The European Wood pigeon and the Stock dove are two migratory species which are both scarce and rare visitors, which have never been documented to breed on the Maltese Islands. In contrast, the Rock Dove frequently breeds in local cliffs, and unlike the other two species, it is a resident species. Unfortunately, it has become very rare to see pure-breed wild Rock Doves in Malta. This is due to the fact that this species has been domesticated for a long time (more than 5000 years) and many varieties and breeds have artificially evolved from it. Feral Pigeons are likely to be descendants of primitive domestic pigeons which escaped, managed to survive in the wild, and interbred with wild Rock Doves.

Feral Pigeons are distinguished from domestic breeds simply because, despite the multitude of colours, their morphology (not plumage) is almost identical to wild Rock Doves. Due to an explosive growth from Feral Pigeons, the species has become an exceedingly common bird on a global scale, but the pure wild race, at least in Europe, is quite rare and has a limited distribution along the cliffs of Northern Europe. In 2001, one of the authors (AS) made an attempt to breed the wild Rock Dove. While the breeding inside Għammieri was successful, reintroductions in the wild seemed difficult because Feral Pigeons have to be eliminated first, and Pure Rock Doves often fall target to Hunters.

Doves are morphologically smaller than Pigeons. Four species visit the Maltese Islands. The largest species is the Eurasian Collared Dove, Streptopelia decaocto, which until recently was considered as a rare visitor but is now an established breeding bird. This species has been extending its range all over Europe and hence it started to arrive here in large numbers and eventually started breeding here. It first established itself as a breeding bird at Għajn Żejtuna; but eventually it started spreading in various localities such as Addolorata Cemetery, Buskett, Lija, Attard, Pietá, Fawwara and even in Comino and Gozo. Given chance, this species will spread all over the islands within a few years because in addition to being a prolific species, migratory individuals have tendencies to join resident flocks. The second largest species is the European Turtle Dove, Streptopelia turtur, which migrates in large numbers but is very rarely granted a chance to nest, even though many attempts have been reported over the years. The third largest and rarest species is the Laughing (or Palm) Dove, Streptopelia senegalensis. Another dove found on the Maltese Islands is the Barbary Dove, Streptopelia risoria (domest.). It is debatable whether this species is a domesticated breed descendant from the African Collared Dove Streptopelia risoria roseogrisea, or a totally different species. This species has bred in the wild via escaped individuals and sometimes hybridises with the Eurasian Collared Dove.

Pigeons and doves are generally weary of humans but a few, including those mentioned, have adapted to live near humans and found urban life more suitable. The European Wood Pigeon and the Collared Dove withstand urban life, but the major cities around the world, are dominated by Feral Pigeons. Can anyone imagine cities without this bird? If it weren’t for mankind, this race would not have existed. Humans managed to raise wild Rock Doves in captivity. When the species became tame, by artificial selection, several breeds and plumages emerged, none of which ever existed before. The purposes of domestic breeds are several, namely as sources of food, such as the Broiler, for competition and sport such as the Homer, and for exhibitions such as fantails, Pooters, Dwarfs, and so on. Feral pigeons obtained the various plumages from domestic breeds, but regained the morphological characteristics of the original ancestors from wild Rock Doves. This species was one of several which also assisted the renowned naturalist Charles Darwin to formulate his theory regarding evolution.

Many people assume that feral pigeons bring nothing but diseases, and these are considered to be a treat to architectural features, statues and buildings. It is true that their urban settings mean that they are not tidy and that their acidic faeces dissolves carbonic structures and to many bird breeders, naturalists and so on, the feral race is seen as a common species without any ecological value whatsoever. On the other hand to those interested in the classification of biodiversity, this race is a clear example of evolution. It is true that when a species evolves, it constantly changes to adapt to its environmental surroundings. The feral pigeon is not only a mix of coloured plumages which decipher nothing, but an array of forms, some of which persisted to exist and continued from one generation to another, in order to become distinct. This means that certain plumages have become standardised, and in some cases reached dominancy. From observations made by the authors, seven consistent varieties have been identified. Locally, the consistent varieties evolved in areas where the species is abundant, such as Valletta, Floriana, Ta' Xbiex, Msida, Ħamrun, Comino and Victoria (Gozo).So far no records or documents exist to show that these varieties are taxonomically recognized, except for the fact that feral pigeons can easily interbreed with wild Rock Doves . It is likely that certain varieties within time can become endemic. This has happened in places around the globe where species have become isolated. The varieties are morphologically pure, but not necessarily genetically pure as they can be interbred with other forms. Although it was noted that birds of opposite sexes are mostly attracted to similar plumages.

The so called ‘varieties’ are the following: nomenclature for such varieties is often colloquially used for describing individual birds in domestic breeds:

- The Blue Bar is the closest plumage to the original, which clearly belongs to the Nominate Rock Dove. The colour is bluish-grey, with two black bands on each side of a wing. Generally, the bands of the feral pigeon are thinner and not often as consistent as those of the Rock Dove. The tail is grey and black-tipped. The neck feathers are shiny with purple and green iridescence. The rump is white. Those very similar to the original are rare.

- The Blue Checkered is similar but is uniformly-dotted on black and on the wing. Common.

- The Dark variety is black from head to the wing-edge, but its rump and tail are similar to that of the original. Common.

- The Red Bar is like the Blue Bar, but whitish-grey while the neck and chest are brownish-red, with red bands of similar shape to those of the Blue Bar. Scarce.

- The Red Checkered is similar to the Blue Checkered but instead of having grey and black, they have a brownish-red pattern. Frequent.

- The Brown variety is similar in pattern to the Dark variety, but with shades of reddish- brown. All of the brown colored varieties have brown veins on their feathers.

The rest of the forms that exist are intermediate between the mentioned consistent varieties, without any uniform pattern. Albinistic and melanistic forms occur. Albinistic flocks of pigeons are restricted to public gardens and farms. Melanistic pigeons are rare on the whole. Very rare forms sometimes seen are the Bronze, which is a likely descendant of the brown variety, and the Bluish-Red Bars are likely to be a cross between the Blue Bars and the Red Bars. Certain individuals are similar to any variety, but have odd characteristics such as white primary feathers, or irregularly placed white feathers on any part of their body, and these are referred to as Pied pigeons. With time, feral pigeon varieties outside Malta have become distinct subspecies. One example is Columba livia atlantis, which is found in Northern European countries along the Atlantic. Another example is found in England, at Trafalgar Square, where the entire population of feral pigeons evolved into the Dark Variety.

In recent years, some cities around the world started to implement measures to reduce the feral population of pigeons. This has become a necessity, in order to control the spread of disease, reduce genetic pollution with the original wild stock, and to prevent further damage to historical architecture. But at least it should be done in a humane or natural manner, such as reintroducing birds of prey that feed on feral pigeons. However, to some people the loss of feral pigeons from towns and cities is a big loss since it has become synonymous with urban infrastructures and societies.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)